I know I promised a write-up on the experience of mercilessly hacking apart and rebuilding your own old novel because it had been an interesting thing to go through, and now, over a week later, I’m not quite as sure of that as I was; I suspect this’ll just be general editing advice. But anyway, it’s the goddamn internet and you can’t stop me.

(Mostly I’ve been busy and/or ill. And while I’m talking about editing I should probably remind you I’m available for hire as an editor very cheaply and very professionally. Anyway, moving on…)

I’d have loved, in an ideal world, to have done the writer’s cut of The Touch Of Ghosts for an actual publisher, Apocalypse Now Redux/Blade Runner style. But then it’s only because it had lapsed out of print that I got the rights back to do it; if it had lumbered along as a middling seller all these years this would never have happened, and if it had been wildly successful Penguin would never have allowed it (because people obviously liked the original).

On the upside, this means I’ve had total creative control over the new edition. On the downside, this means I’ve had total creative control over the new edition. Still, I dug the thing up, hauled it out into the light, and got to work on resurrecting it, and I don’t think I did a bad job. Let’s have a look at the rough stages, shall we?

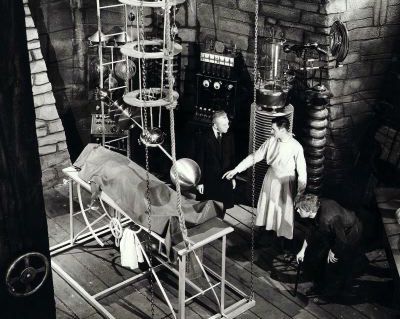

1. Preparing Your Creation

Before you get your physical specimen on the slab, or on a first preliminary look at worst, you should have an end result in mind. You have to bear in mind that this isn’t like a redraft of a novel that’s yet to see the light of day. You can’t just rip the whole thing up and start afresh, because you are - and might as well be - writing something else instead.

I have a freakishly good memory within certain mostly-useless fields. I can remember, looking at the book for the first time since the final galley proofs came through nine and a half years ago, which bits were first draft, which were second or third. I can also remember what I’d originally wanted from the story. You might not have this; but a cursory read-through should show you what the core of it is, which sections ignore this entirely, and what you need to expand upon to add to it. What should be the headline act? What are the cool support bands? Which bit’s Coldplay?

Basically, you need to know before you start cutting what you want the end result to look like. I knew the story should be, at heart, about loss and not about solving a mystery.

2. Examining The Specimen

Once you have the physical body on the slab in front of you, you can start going through it, piece by piece, deciding which bits to keep and which aren’t needed. What you need more of, what you need less of. Some of this will be general editing, some will be altering the beast into the form you want.

I ended up with four pages of notes on TTOG. I knew what I wanted to do with the story, so now I was looking to see what worked and what didn’t, both in general and specific to the change in focus away from the whodunnit and on to the emotional, psychological heart. Let’s see some examples taken from the top:

"Change prologue!" (With some notes on what style to change it to.) The one in the original version is perfectly serviceable, but was added in at draft 2 to put more action at the start of the story (it shows what happened to one of the earlier victims of events). I wanted something else there, something that would hold a thread through the whole book.

"First chapter line/intro much better." The opening does a lot of the character establishment heavy lifting, but it’s a bit dry. I mostly fixed this, in the end, by substantial cuts to shorten the opening section. I toyed with the idea of using a flashforward/back structure wrapped around Alex (spoiler-free description follows) examining the place where a car has left the road, covering the events leading him there in flashback scenes bracketed by his increasingly focused investigation of the ground. Stylistically it would have worked, but there wasn’t actually enough material in that scene - and it comes late enough that it would have been hellishly confusing for the reader when the two time threads joined - to make it worthwhile. So, trimmed and neatened, and with a new first sentence, I left this alone.

"TRIM! Esp. descriptions of Al’s stuff." One of the changes in my writing style down the years has been to move away from the "First I got up, then I had a piece of toast. It was good toast, not too brown, and it had butter from a little craft dairy on it." school of description. There was too much faff, too much needless physical description (it’s not so bad for the rest of the cast, but do you really need to know the main character’s jacket colour?).

"[CHARACTER] = [SPOILER]". I can’t give away this one without spoilers, but this was something I’d wanted to do with one of the minor supporting characters that my editor at Penguin nixed. It would have shown just how fragile/broken Alex’s psychological state had become in a cool little way, I thought. She said readers would never buy it. This change I reverted, but it was hard to do given that they’re only a minor character and the reveal couldn’t be too overt without distracting from other events when it happens.

"Conflict with Vermont State Police." Turning it into a whodunnit had made the police, by necessity, very chummy with Alex. In reality, they shouldn’t want him around because, hey, you’re screwing with an investigation here. This was a major missed opportunity for a bit of drama, a bit of friction. It needed to be in the story. It wasn’t in my first draft, though; I hadn’t twigged to the idea back then.

3. Excisions

Now you can go through and cut like a maniac. Take out everything that needs to go, pickle and preserve any information that needs to be in the story to keep the plot rolling along but which can’t stay where it is or in the form it needs to be. Lose everything that needs to be lost. Where you need more of something, or you need a whole scene written from scratch, do so. Prepare it for insertion. Check against what you’ve planned. Mop the sweat from your brow. Demand forceps, swabs, fresh gauze.

TTOG started off at about 85,000 words. The writer’s cut version is about 60,000 words, a few thousand of which are new. The amount I had to take out was therefore pretty huge, most of it because it was junk, some of it because without the bits either side of it, while OK in itself, a section didn’t need to be there any more. But I didn’t have to meet the demands of hardcopy display on bookshelves, where a certain width is considered vital. It also meant that reducing the plot’s complexity didn’t slow the pace. The new version is, if anything, nippier, because there’s not so much talking-in-rooms going on.

4. Stitching

Once the various bloody lumps are in roughly the right shape and the right place, you can sew them together. You want to make it so the joins are perfect, not loose, weeping, strung together with massive twists of catgut. Make sure all the scenes, new bits and surviving old bits, all flow seamlessly into one another. If your writing style has changed down the years, you need to be either doing a good impression of your old self or else have polished the old stuff to look like your new. It’s like reworking a film using updated CGI - it’ll look silly if it’s clean and perfect and everything else is falling to bits. Mr Lucas.

I had to monkey repeatedly with one chapter, which could’ve slotted in at just about any point in the midsection. Finding the place which fit best, suited the pacing and the timing, and then smoothing over the joins took some doing. The rest was relatively easy, in part because I was line-by-lining it anyway to change the tense the book’s in.

5. Evaluation

Now have a look at your creation. Does it match what you wanted in the beginning? Is it as good as you can make it? Bearing in mind, of course, you’ve only got the one body to work with and there’s only so much you can do with the original material. Is it better than the original? Because if it’s not, you need to look again.

The new cut of TTOG is better for sure than the old. The stuff that’s gone… well, I’m amazed a lot of it got the green light from my editor. Amazed that I was paid money for it. For instance, the original version of the ending few chapters included several muddled “I heard about X from Y” joining-the-dots remarks where X and Y had changed between drafts 2 (Alex is told about the escaped monkey by the man at the zoo) and 3 (Alex finds out that there’s a monkey on the loose when it steals his banana sandwich) and so the text contradicted itself (“The guy at the zoo told me about Coco,” I said. / “No he didn’t,” the other person replied. “Coco nicked your sandwich. You’re suffering draft-related amnesia.”), but no one ever noticed.

There’s none of that in the new edition. At least, there’d better not be.

Oh, yeah, and the actual writing is better, characterisation’s more focused, events are less shoddy, the drama’s more contained, and all that.

6. Life! Life!! GIVE MY CREATION LIFE!!!

If it’s what you wanted, if it’s as good as it can be, all you need to do is pump 20,000 volts into it and set it loose upon the poor, unsuspecting, pitchfork-armed locals while you raise a steaming flask of green SCIENCE down in your lab and congratulate yourself on a job well done.

Cheers.

Addendum: Future Abominations

The other two old books represent two different challenges. The Darkness Inside never strayed from its original template and the core concept and the thread that carries it is good. It just needs a bit of a tidy and a change to past tense. (My notes on that one amount to one page, most of which are one-liner suggestions.)

Burial Ground, though, changed almost entirely from its first draft. I’d set out to write a survival horror story (with all that that entails) thinly disguised as a thriller, but my editor was not a fan of that as a genre. While some of the end changes made for a better story (better characterisation, etc.), at the time I was hugely disappointed that the final draft was just another Alex Rourke book and not what I’d hoped for. I was pretty bummed at having to knock out the same sort of thing time after time. Now, it just so happens that I have all three drafts of BG on my computer still. I’ve not gone through them yet, but it’s entirely possible I might be able to get back to what I’d wanted via some kind of hybrid of first and final…